← Back to June 2025 Newsletter Contents

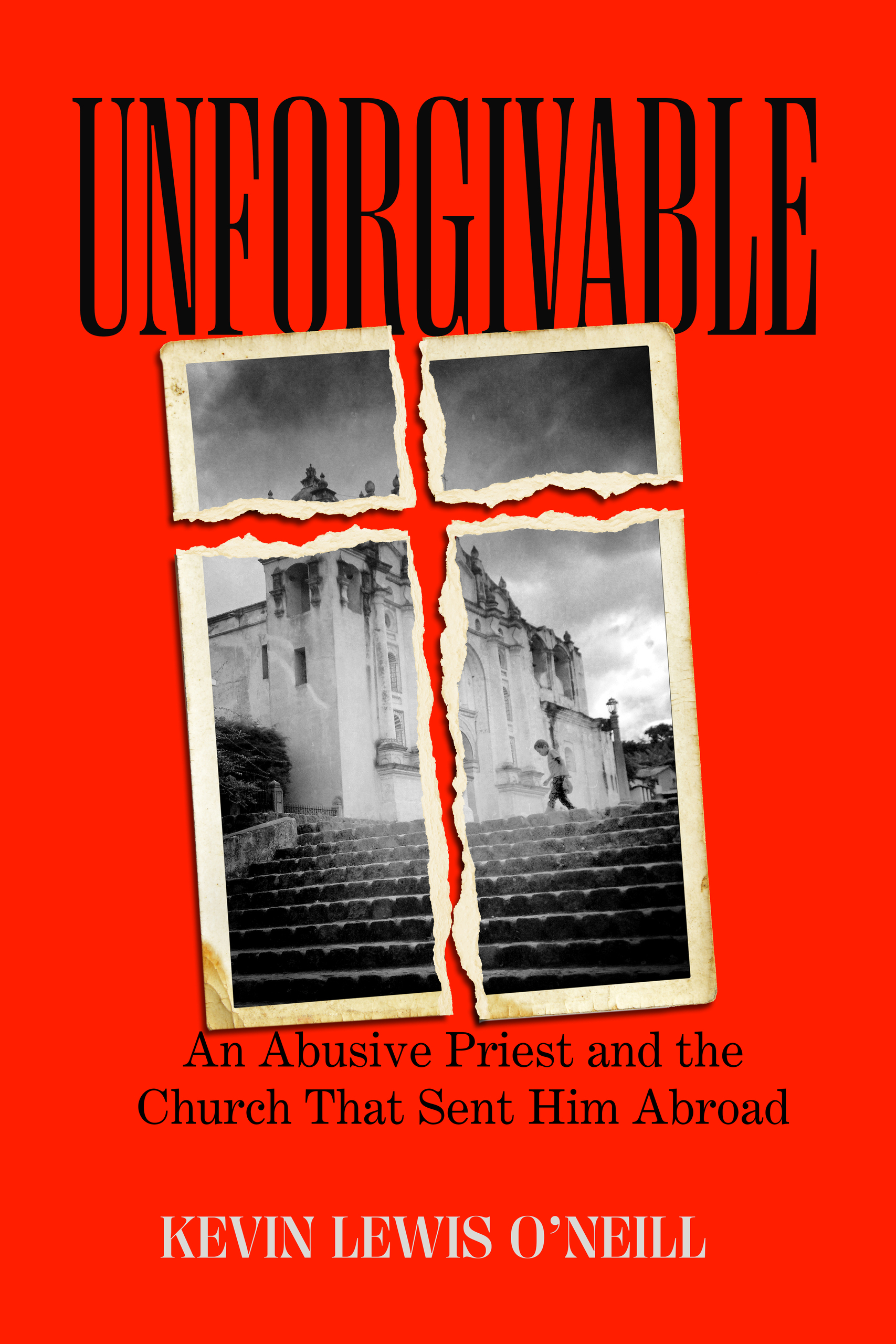

Cultural anthropologist and 2021 John Simon Guggenheim Fellow, Kevin Lewis O’Neill is professor in the Department for the Study of Religion and the Centre for Diaspora and Transnational Studies. His most recent book is Unforgivable: An Abusive Priest and the Church That Sent Him Abroad (University of California Press, 2025).

We asked Professor O'Neill about his academic and personal paths to this important and disturbing work – and explored, too, how the research and writing of the book came to intersect in unexpected ways.

You are a cultural anthropologist and this book is described by Laurence Ralph [professor of anthropology at Princeton University] as “explosive ethnography.” Could you explain the difference between cultural anthropology and ethnography?

Sure! Culture Anthropology is a recognized discipline of study like History or Mathematics. Students can major or minor in Anthropology, for example. I did my PhD in anthropology. Ethnography is a research method that cultural anthropologists tend to use. Ethnography usually involves immersing oneself in a place or with a group of people through informal interviews, open-ended conversation, and sometimes even archival research. Anthropology’s biggest wager is that ethnographic research can tell us something unique about the world we live in.

Your work has focused on contemporary political practice in Latin America, examining its moral dimensions, with particular emphasis on Guatemala. How did your specific interest in that country come about?

Anthropologists sometimes come to their field sites through incredible moments of discovery. Some even narrate it very romantically, like it was love at first sight. My interest in Guatemala has always been more like an arranged marriage, in the very best of ways. I was interested in religion and politics as a graduate student, and I had also traveled (a bit) in Latin America. One of my advisors at the time said that I should check out Guatemala, which had just ended a 36-year genocidal civil war. The country had also begun to experience a dramatic shift in religious affiliation: from Roman Catholicism to a Christianity called Pentecostalism. I spent a summer there in 2001, and now (almost 25 years later) I couldn’t imagine working anywhere else.

What did you want to achieve with Unforgivable and did your intentions change as you became immersed in the topic?

What did you want to achieve with Unforgivable and did your intentions change as you became immersed in the topic?

My intention has always been to demonstrate that clerical sexual abuse is as global as the Roman Catholic Church. Lawyers and journalists have largely defined what we know about clerical sexual abuse, with very little scholarship available on the topic. What lawyers and journalists in the United States (and elsewhere) routinely find is that Church leaders move perpetrators from parish to parish in the hopes of evading a raft of responsibilities. As an anthropologist, I have been able to expand the frame to identify instances in which Church leaders also moved perpetrators across international borders. Unforgivable engages the movement of a prolifically abusive priest from Minnesota to rural Guatemala. It is a frighteningly common maneuver but one that very few people have documented, let alone theorized.

The detailed and close research involved in Unforgivable, as well as the importance of relationship building with its central subjects – most particularly the survivor whom you call Justina – is for the non-specialist reader reminiscent of investigative journalism. In the last part of the book, you shift from a third to first person narrative. What happened during the research process to prompt the decision to so directly include your own experience in the book?

Not surprisingly, the priest from Minnesota continued his abuse in Guatemala, even raising an orphan girl as his own for nearly a decade. I call this girl (now a young woman) Justina. My research along the way took two modes. The first was archival in the United States, where I found a lot of information about the perpetrator and could piece together a good sense of him. The second is probably best described as investigative and took place in Guatemala, where I have completed fieldwork for nearly a quarter of a century. It was investigative (rather than just ethnographic) because I knew certain facts from the outset: the priest in question was a sexually violent man, he had moved to Guatemala, and he had raised Justina for nearly a decade. That’s more certainty than most ethnographers have when they begin their projects, and so I was able to pursue how this priest ended up in Guatemala and the effects of his stay there. I would just also add a distinction between my work and investigative journalism. It is that I advance a scholarly claim about jurisdiction and ontology that exceeds the interests of a general audience. Unforgivable is a philosophical argument that has the feel of long-form journalism.

Is there a way to reconcile the difficulty of exposing this abuse without also exposing survivors to the scrutiny of their communities – a particular factor in a remote community such as Justina’s? Even without the personal feelings of shame it often engenders, there is a fundamental consideration of an individual’s privacy.

The other big difference between investigative journalism and something like investigative ethnography is its time horizon. Journalists have deadlines. They also want to be out in front of a story. They work fast and for good reasons. Unforgiveable took about ten years to complete, from start to finish, and university presses generally don’t care when a book gets published. This allowed for a very slow conversation with Justina and one that advanced at her pace. Near the end of the process, she read a Spanish translation of an advanced draft, but the draft came after years of discussion as to whether and then how she wanted to be a part of the story: what she felt comfortable sharing and what she wanted kept private. In the end, she made the incredibly brave decision to be a part of the book.

Do you think there is any possibility of the Church making meaningful amends for the damage its actions – or indeed, inactions – in this sphere has caused? What might that look like?

It’s difficult not to be cynical about the Roman Catholic Church and its systematic protection of sexually violent priests. It’s also devastating to realize that we only know a small fraction about the Church’s abuse and its stunningly sophisticated techniques to evade accountability. What might it mean for the Church to make amends? Lawyers in the United States have cost American dioceses and religious orders more than $6 billion in settlements so far. But the United States’s culture of litigation is unique, and civil suits of this kind are not possible in other parts of the world. Settlements are also neither admissions of guilt nor gifts from the heart. They are forms of compensation. In the end, an effort at amends could mean the Church drawing from its own theological vocabulary to ask—really ask—for forgiveness. I’m not hopeful.

Your interest in continuing to work on this topic is described on your website as taking the form of a book on “a global history of sexual abuse that begins near the Badlands of New Mexico.” Tell us more about that.

The priest from Minnesota who moved to Guatemala passed through a Church-run sex therapy center in New Mexico. A religious order known as the Servants of the Paraclete operated the center and dozens more around the world, from Bolivia to Tanzania to Rome. They even bought an island in the Caribbean for the most incorrigible of these guys. The Servants of the Paraclete basically offered an in-house solution to what Church leaders routinely call the “problem of the problem priest,” but in the end they made the problem worse, moving sexually violent priests (for example) from Minnesota to Guatemala.

Tragic, violent, and sometimes unbelievable, this network of centers allows for a global history of sexual abuse: a chance to move beyond the singularity of so many heart wrenching cases to see the entirety of the Church’s strategy.