In March 2025, our final guest in the 2024-25 DSR Lecture Series was University of South Carolina historian of religion Marko Geslani, who specializes in ritual studies and medieval Hinduism. He delivered “Vindication of Invention: World Religions to Lived Religion,” which queries the rude reception by scholar Robert Orsi of Tomoko Masuzawa’s study, Invention of World Religions (2005), as backdrop to the project of “lived religions.”

An associate professor in the Department of Religious Studies at the University of South Carolina, Geslani is the author of Rites of the God-King: Śānti and Ritual Change in Early Hinduism (Oxford University Press, 2018). His current research includes exploration of the role of the astral tradition (jyotiḥśāstra) on the problems of personhood and state formation in early Hinduism, as well as a racial critique of the study of Asian religions as a setting for new approaches to Orientalism and premodern Asian studies.

On his visit to U of T, Geslani sat down with DSR PhD student Sarang Patel, whose research interests lie in the anthropology of Hinduism, for a conversation that included Geslani’s scholarly trajectory, the relationship between pedagogy and research, and the challenges of describing a ritual culture.

Rites of the God-King, your first book, tells an alternative history of the Hindu ritual of image worship. What brought you to study the relationship between “Vedism” and “Hinduism,” and more generally to first millennium religion in India, ritual studies, and Indology? Does one begin by choosing a tradition, time period, or methodology, with a nagging worry or question, a combination of all these, or something else entirely?

I began my undergraduate in religious studies on the side of Jewish studies and early Christianity. I was in the Arts & Science Program at McMaster University, and it had an (Eastern and Western) civilizational component which put me in a classical frame of mind. Language learning was key. And it seemed like religious studies was a culturally more interesting way to study the classical world. I started learning Hebrew, and went on to study intro Sanskrit as well.

My first introduction to Hindu studies was reading the Purāṇas in translation. Phyllis Granoff, who was at McMaster at the time, would have us read hundreds of pages of these texts, so I had a feel for Purāṇic literature and the Māhātmya tradition. My earliest interest was around pilgrimage, sacred space, and the ways in which Purāṇic stories relate to geography.

When I moved to Yale, I began working on a project on the Vāmanapurāṇa and the tradition of ritual bathing in Kurukshetra. I was trying to understand why people bathed on solar eclipses. That’s what got me into the astral tradition.

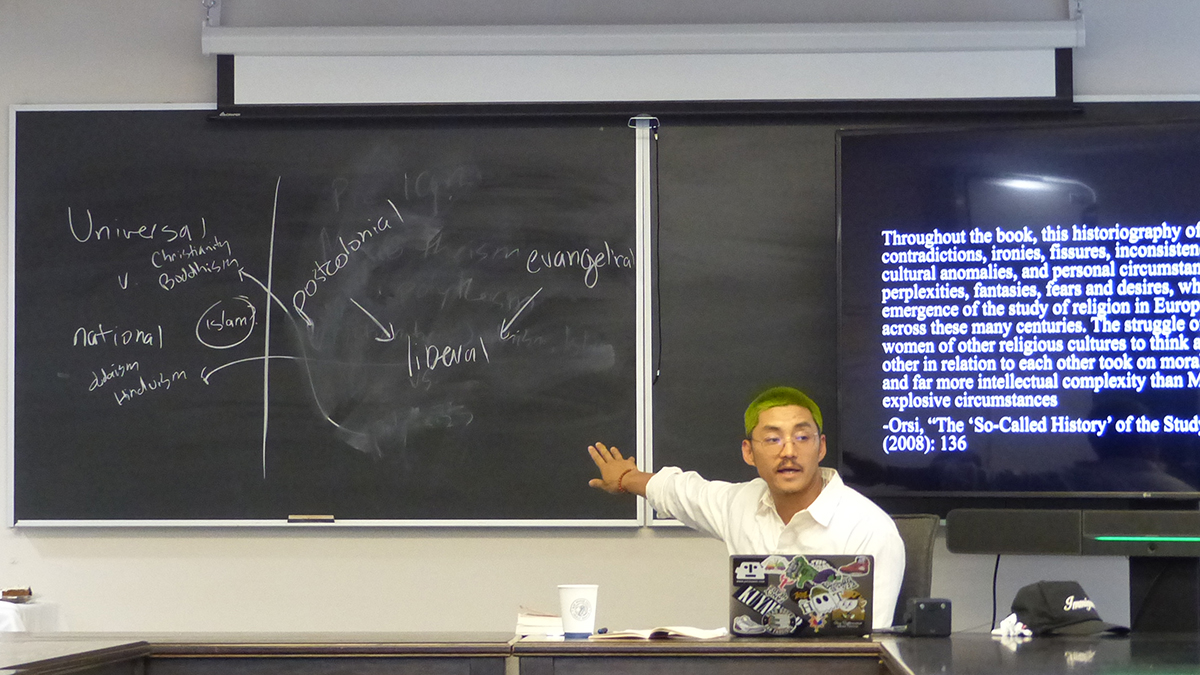

The classroom is the closest I come to a public that would care about what I do. It’s the most obvious site of accountability for me.

The nagging question that emerged was, what is the nature of Purāṇic praxis? There was a shift in my mind from thinking about place and geography to thinking about ritual timing. I found there was a kind of ritual culture here that is not tied to sectarian movements. This pushed me to the intersection of Vedic domestic culture and the astral tradition. In other words, the question was, how does one describe a ritual culture?

The question of the relationship between Vedism and Hinduism also becomes pertinent here. Vedic and Hindu religion have generally been strictly distinguished based on the supposed irreconcilability of the aniconic Vedic fire sacrifice (yajña) with image worship (pūjā), and Hindu theism more generally. The kind of ritual culture I was trying to describe in the interstitial ritual manuals known as the Pariśiṣṭas overlapped with and informed temple culture (including image worship). The terms Vedism and Hinduism were pushing us away from looking at these kinds of sources.

Rites of the God-King begins by reflecting on pedagogical choices in a North American college classroom. What role does attending to such choices play in your work? How does teaching inform your research?

You usually write an introduction last. The book began as a dissertation in the deep recesses of the library without any consideration for pedagogy. When I began writing the introduction, I had already been teaching for a while in a liberal arts setting. The classroom is the closest I come to a public that would care about what I do. It’s the most obvious site of accountability for me. To the degree that graduate students and active teachers of Hindu studies would read the book, beginning in the classroom was my attempt to say this is what we do as a guild, isn’t it? We teach this way. That is the point at which our scholarship becomes a public act of representation, where Orientalist knowledge turns into a form of cultural representation. Attention to how we teach has become an ethic in my scholarship – the final stakes of how we think translates into a pedagogical purpose.

You usually write an introduction last. The book began as a dissertation in the deep recesses of the library without any consideration for pedagogy. When I began writing the introduction, I had already been teaching for a while in a liberal arts setting. The classroom is the closest I come to a public that would care about what I do. It’s the most obvious site of accountability for me. To the degree that graduate students and active teachers of Hindu studies would read the book, beginning in the classroom was my attempt to say this is what we do as a guild, isn’t it? We teach this way. That is the point at which our scholarship becomes a public act of representation, where Orientalist knowledge turns into a form of cultural representation. Attention to how we teach has become an ethic in my scholarship – the final stakes of how we think translates into a pedagogical purpose.

How did your interest in critically reflecting on religious studies as an academic discipline emerge?

It emerged from my experience in the classroom, and at a specific moment—the moment of Black Lives Matter. What does it mean to be an Asian person teaching Asians about Asian religions in the American South during the age of Black Lives Matter? More generally, in the context of secular pluralism, what kind of work is that doing? It was an embodied response ultimately to my sense of the political imperatives that were demanded of us as Asians in those classrooms at all levels. It was following my feeling of discomfort first of all as a brown body, but then as a brown body that is teaching other brown bodies in a position of liberal authority. I’m trying to write in a way that creates space for myself as (Filipino) Asian American. If we can create space for ourselves from multiple positional perspectives (race, caste, class, gender), the fields of Hindu studies, South Asian studies, and Asian studies more generally can be more capacious.

You have several books in the works. Can you tell us a bit about them? How does one manage multiple projects that range so widely?

The working title of the first book I am working on is Stellar Kingdoms. This is the book I wanted to write immediately after Rites of the God-King. I wanted to go deeper and more comprehensively into Varāhamihira’s canon because I think he is such a consequential polymath. I am trying to bring the question of the consolidation of the astral sciences into the frame of religious studies. Right now, what is most exciting about the project is that Jyotiḥśāstra (the astral tradition) was negotiating a place within the Brahminical political-legal tradition, which suggests it has a function for the Brahminical state. I articulate a wartime-peacetime structure, suggesting that Varāhamihira was trying to routinize a way of representing warfare, so to speak, in the ritual calendar of the medieval state.

As I have been working more on the critical racial and colonial side of our field, my second book Orientalism for all the Orientals! has taken over. I have come to the feeling that I would like to figure out my politics before returning to being a Sanskritist. What could I write about Jyotiḥśāstra that is not just for Indology or South Asian studies? One thing that comes to mind: a Brahminical aesthetics informed by the astral sciences is absolutely relevant to the question of Asian aesthetics more generally. In my mind, the best version of the book on Jyotiḥśāstra would be speaking both with South Asianists and at least theoretically with Asian Americanists as well. I am attempting to experimentally write my own version of an Asian American Orientalist project that speaks to different historiographical traditions differently interested in the question of Asia.

The third book, Disinterring Geertz, is a COVID-era project that I am co-authoring with Tulasi Srinivas. It was conceived on a Zoom call following an AAR book panel. We both felt that there was a kind of quiet in ritual studies after the devastating critiques of the category of ritual and symbolic anthropology. We’re trying to do a South Asianist reading of the field in a way that revives the category while remaining responsible to its genealogy in the colonial encounter in South Asia. The book is a dialogical work between an ethnographer and a philologist.

My work on these three projects reflects what I am thinking about at the moment, so even though I dedicate separate time to them, they’re not necessarily separate. Each project is enriched by the thinking involved in the others.